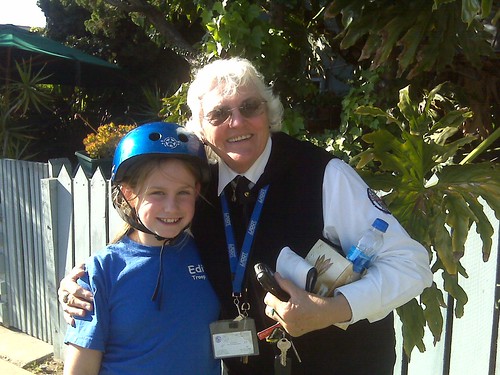

Last March, Betty Jolley retired after 32 years as a crossing guard in Venice Beach. Elano Pizzicarola, a student journalist and journalism major at Cal. State Northridge, interviewed Betty and has piece to share.

From Elano Pizzicarola:

What does it take for someone to work as a school crossing guard for

32 years? Elizabeth Jolley, who has just retired from that very job in

Venice Calif., knows the answer. “Dedication, I suppose,” says the

English native, who just turned 76 last March.

She was liked by the whole neighborhood where she worked. The kids

adored her, and their parents trusted her. Many, who had grown

accustomed to seeing her at the corners she worked, had to see her

leave. It was an emotional period they struggled to endure. So when

Jolley was selected to be part of the cut, rumors about her retirement

spread.

“They were very, very disappointed,” says Jolley, who got up from 5:30

a.m. to a quarter to six, never late to her job or absent once.

Parents responded with gifts like chocolates and flowers, bringing

them to Jolley during her last days on the job.

Jolley’s retirement came due to the recession. Last November, the City

of Los Angeles launched a cost-cutting measure, allowing early

retirement to 2,400 of its workers. And as for Jolley, despite her job

giving her “vitality,” she knew she couldn’t work forever. So during

that same month, Jolley, who worked at both Saint Mark School and

Coeur d’Alene Elementary School, took up the offer and applied for the

program. Last February, Jolley found she was finally selected for

retirement.

Despite Jolley wanting to work till the end of the school year, she

was forced to leave on March 12.

“So that was my last day, the twelfth of March,” says Jolley, which is

what she remembers most.

Jolley’s final day yielded a celebration. It garnered local media

attention, as CBS News showed up at the gathering. And at the day’s

end, Core d’Alene granted her a plaque for her work on behalf of the

school and the families of students who went there. “It was, like you

say, ‘I had my fifteen minutes of fame,’” Jolley says.

“It was just a wonderful day.”

Jolley has lived in the same 97-year-old home near Abbot Kinney Blvd.

for 44 years. She has driven the same 1994 Toyota Corolla since its

release.

“I guess it was just the way I was raised, the way I was born,” Jolley says.

In Bradford, England, before Jolley turned 12 when her family moved,

she lived in what she calls a “back-to-back” house, with two living

spaces attached. It was surrounded by bucolic open fields with lambs,

cows and horses.

Jolley family’s living space had two bedrooms, one of which she shared

with her brother, Kenneth. To bathe, she was forced to use a tin

bathtub that was about four feet long, affront a fireplace. To use the

bathroom, she would have to walk to a toilet, outside her house, that

she shared with her neighbors who lived in the house that was

adjacent. To cook, her family would have to use a cast iron device

that she calls a “Yorkshire range,” that served as an oven, grill,

water steamer and heater for her home.

“You walked to the end of the street — there were a row of toilets

back there. You usually shared one toilet with the people that lived

behind you,” says Jolley who happened to live close to the toilets,

shortening her walking distance. During the snowy winters, and

frequent rain, her and her family used what she calls, a “chamber

pot.”

“That’s how people lived in those days, unless you had a house with a

bathroom,” says Jolley, understanding that this lifestyle may seem

foreign to generation X and Y.

At 10, Jolley wrote in a school notebook that she wanted to move to

the Golden State. And by 12, she wrote to the film studios, asking

them to mail her celebrity photos.

Back then, videotapes were nonexistent. So Jolley frequented movie

theaters, as many did in Bradford. When she was 25, she moved to New

Zealand, and worked in the wool mills as many of her peers did.

“We left school and started working straightaway. We never had the

opportunity to go to college,” says Jolley, who began in the office,

but moved on to the mill to earn far more money.

But in 1961, Jolley’s dream to move to California was answered, thanks

to family friends sponsoring her, which she says, is how it was done

back then.

“It wasn’t easy coming to the United States in those days. You had to

go ‘the counsel’ and have a medical exam and a background check-up and

fill all the paperwork out,” says Jolley, who embarked from New

Zealand on the two-week voyage without her family.

“They weren’t too happy. My father was — I think — disappointed.”

Nonetheless, on July 23, 1961, after stops in Honolulu, Vancouver and

San Francisco respectively, a 27-year-old Jolley, aboard the Canberra,

Maiden Voyage, arrived at the Long Beach Port. Her eyes were used to

Bradford’s cleaner air, so they were irritated by the smog before the

ship even docked.

During Jolley’s stay, she first got a job babysitting six children,

for a doctor in Brentwood, where she experienced the 1961 Bel Air

fire. Eventually, she met her future father-in-law, Jack, who used to

be a film projectionist in Santa Monica. Jack introduced Jolley to his

son, who shared his father’s first name. But before they married,

Jolley became homesick and traveled back to Bradford, living back home

for a winter.

Two months later, Jolley returned to Los Angeles and finally married

Jack Jolley in 1963. And ten months after that, Jolley and her husband

Jack, who worked in space exploration, gave birth to her first child.

A doctor noticed that the newlywed’s daughter, Gloria, suffered from

breathing problems. The doctor suggested that Gloria be closer the

ocean, breathing cleaner air. So, in 1966, the family moved from

Palms, Calif. to Venice.

Her husband, who worked in space exploration, had preferred her to be

a stay-at-home mom. But one day in Jan. 1978, one of Jolley’s

neighbors, whom she remembers as “Linda,” had been job hunting. Jolley

noticed an advertorial in Santa Monica’s 123-year-old Evening Outlook

newspaper, which stopped printing in March 1998. Jolley shared the

blurb with “Linda,” but her neighbor declined the offer.

Jolley recognized how this job would be apt for her lifestyle, as she

could work when her children were at school and return home before her

kids, still tending to them, as her husband wanted.

And later that year, after an interview at the Venice Police station

on Culver Blvd. and a visual service exam at Hollywood High school,

Jolley began a 32-year career as a crossing guard at 44-years-old.

Jolley’s first stint was at Broadway Elementary School on Lincoln

Blvd., where she biked from her nearby home. She was trained by a

woman in her late 40s, maybe 50-years-old. Jolley calls her by her

first name, “Rita,” as she is unable to remember her last name.

“And then, I was on my own after that first day.”

When Jolley began her career as a crossing guard, her kids, Erick and

Gloria, would react with excitement. But as the siblings aged, both of

them now working in the entertainment industry, realized the risky

environment their mother worked in and grew concerned.

“They used to say, ‘It’s such a dangerous job, mother. I wish you

didn’t really do it,’” says Jolley, who respond with an affectionate,

cheerful “‘I love doing it,’” her son and daughter, still wary.

“So they day I decided to retire, they were very, very happy – very happy.”

Jolley worked five days a week, sometimes during summer school. She

liked working during summer less than other times, for Jolley

preferred to vacation back in England when school was out.

Six years into her career, Jolley was transferred to Coeur D’Alene

Avenue Elementary School, which was closer to her home, walking to and

from work. She also worked as a crossing guard for Saint Mark

Elementary School, which was about a block and a half away from Coeur

d’Alene. She worked for both schools, corresponding to their end

times.

Today, Jolley, a book-lover, volunteers at the Coeur d’Alene library

on Wednesdays. She helps students check-in their books, reads to them

and stocks the shelves.

“I read books all the time,” says Jolley, who was met, sitting at a

small table in a Studio City Coffee Bean and Tea Leaf, her blue eyes

consumed in Alexandra Ripley’s “Scarlett: The Sequel to Margaret

Mitchell’s ‘Gone with the Wind.’”

And in Venice, sometimes at the library, the parents who trust her and

students who adore her still express nostalgia towards Jolley,

yearning for the time when she was a crossing guard.

Andrew Jenkins, 44, is Coeur d’Alene’s principal. He agrees Jolley

takes the same work ethic from her crossing guard job, to the library.

“She is a dedicated woman in any capacity,” says Jenkins, who was the

one who physically handed her the plaque on that special day of her

retirement.

Jenkins also noticed Jolley at her job site long before her start

time, while balancing her responsibilities of reliability, with

getting to know the students personally. “She was very serious and

very caring,” he says.

Living in Los Angeles, Jolley is still fascinated by the film

industry. But Jolley disassociates herself with many of Los Angeleno’s

needy lifestyle traits of switching residence as income increases,

cars when their trendiness wanes and jobs when better financial

opportunities present themselves. “I’m not that way. I’m British — I’m

English,” Jolley says.

“I like stability. I don’t like to always be moving and changing jobs.”

Jolley does not want much in life besides “peace,” “happiness” and

“contentment,” she says.